This speech was given by Sheila Jeffreys at the Andrea Dworkin Commemorative Conference, April 7, 2006. This original transcript was prepared by another radical feminist (blog now defunct).

Audio version of this speech is available on Sheila Jeffreys’ website.

Hello everybody, it’s terrific to be here, and to be invited to be here, for this Commemoration of Andrea Dworkin, because of course her politics and her writings have been enormously influential in my life. And in fact, in Melbourne, we did have a little commemoration in a seminar series that I run, last year, and thirty-five women came together to read from various different books of hers saying how much they meant to them, and we got a great deal of what we have been hearing about here from Clare, which is women talking about how their lives were broken, and how reading the work of Andrea Dworkin healed them because of abuse and so on. So we got a great deal of that at that evening seminar.

Now obviously a lot of my work has been about pornography and is now about prostitution, fighting prostitution as a form of violence against women, and so Andrea’s work on pornography has been enormously important to me and in fact, in London in the late 1970’s, in 1977, I was involved in setting up the first anti-pornography group in Britain, which was the Revolutionary Feminist Anti-Pornography Consciousness Raising Group, the London Revolutionary Feminist Anti-Pornography Consciousness Raising Group. Yes, it doesn’t roll off the tongue! But by the time I was involved in setting up a central London Women Against Violence Against Women in 1980 I had found Andrea Dworkin’s book on pornography and that was enormously important to me.

However, I thought today, lots of people will be covering Andrea’s work on pornography, and therefore I’m going to do something a bit different, I’m going to look at two of her earlier works, her first published work which is Woman Hating from 1974, which she was involved in writing for a couple of years before that. So this is a truly early work, she was 27 when it was published, so it’s really, it’s a quite extraordinary work, if you think about being able to produce a book of that kind at that age. So I want to look at that and talk about how inspiring that was for me in the writing of my book last year, Beauty and Misogyny, that text was really important for me.

And I also want to say a little bit about Right Wing Women, which is another very important book, from I think 1977.

Now, when I became a feminist, in the early 1970s, I wasn’t aware of Woman Hating. The book was about to be published but I didn’t find it at that time. But in the UK the whirlpool of ideas that Andrea Dworkin encapsulates in Woman Hating was the powerful basis of the feminism that I was developing. It wasn’t until later that I discovered these books, with gratitude, and was able to use them. Now, what’s so radical about Woman Hating, is that the book directly opposes the sadomasochistic romance that creates femininity and masculinity and provides the basis of male domination. Now, when I talk about femininity and masculinity, unlike the sort of modern postmodern trendy craze of saying that you can choose and swap genders and so on, I understand femininity and masculinity as the behaviours of male dominance, masculinity, and female subordination, which is femininity. They are actually about behaviours in a hierarchy of power, so I just want to say that quite straightforwardly. I don’t think gender encompasses that term and I’ll have a go at the whole idea of gender later on.

Now, in Woman Hating Andrea Dworkin speaks of foot binding at some length, there is a very useful piece on foot binding in there, but I think what she says about foot binding works just as well for high heeled shoes, particularly the high heeled shoes of the moment. And she writes that through the crippling of a woman, a man, quote:

glories in her agony, he adores her deformity, he annihilates her freedom, he will have her as sex object even if he must destroy the bones in her feet to do it. Brutality, sadism and oppression emerge as the substantive core of the romantic ethos. That ethos is the warp and woof of culture as we know it.

Now I think that is the fundamental message of Woman Hating, and I think it’s wonderful stuff, you can see the power of Andrea’s language in there.

Now, she analyses in Woman Hating the idea of beauty as just one aspect of the way women are hated in male supremacist culture, and she indicts woman-hating culture for the deaths, violations and violence done to women, and says that feminists look for alternatives–ways of destroying culture as we know it, rebuilding it as we can imagine it. I think the word destroying is strong, it’s good, and it’s crucial. We’re not talking about tinkering at the edges of culture, and what I’m going to ask you to think about today is how we destroy what is called, sometimes, gender, maybe sex roles is better. I’ll suggest to you sex roles might be better, and certainly destroy masculinity and femininity, not tinkering at the edges but we have to destroy them. And that’s what Andrea’s book asked us to do. Hardly anybody speaks in that kind of language now. Today such talk of destroying culture is much rarer than it was then, because we’re in a very conservative time. We’ve all learned to moderate our language now I think, a little bit. Andrea didn’t moderate her language, really; during the whole course of her writing she refused to moderate. The necessity remains to destroy culture, but the optimism of the early 1970s about the possibility of radical social change no longer really exists, I suggest.

Now when researching my most recent book, which is Beauty and Misogyny, I searched for feminist writings which were clear and unequivocal on the harms of and need to eliminate what are considered natural beauty practices in the West. And to my surprise, they were very hard to find. I think that I had overestimated the extent to which the sort of radical politics that Andrea Dworkin possessed, and that I possessed too, in the early seventies, were actually written down. Andrea did write them down, but then when I looked for politics that radical on beauty practices I didn’t really find them anywhere else. The only other person I found with such strong politics was Sandra Bartky from the late 1970’s. But otherwise, it wasn’t there. And I have to say that I don’t think Naomi Wolf really counts in that she was a lot later, but radical I don’t think that book is. We can discuss that if you would wish.

Andrea Dworkin sees beauty practices as having extensive harmful effects on women’s bodies and lives. Beauty practices, she says, are not only time wasting, expensive, painful to self esteem, rather, quote:

Standards of beauty describe in precise terms the relationship that an individual will have to her own body. They proscribe her mobility, [think high heeled shoes, tight skirts] spontaneity, posture, gait, the uses to which she can put her body.

And then she says, in inverted commas:

They define precisely the dimensions of her physical freedom.

Now that’s crucial to me, I do wonder how women are able to be totally imaginative, creative and create a new future for themselves in their minds, if their bodies are totally tied down and completely constricted. That seems a crucial understanding. Beauty practices aren’t just some kind of interesting optional choice, extra, but they fundamentally construct who a woman is and therefore how she is able to imagine, because they constrict her movements and create the behaviours of her body.

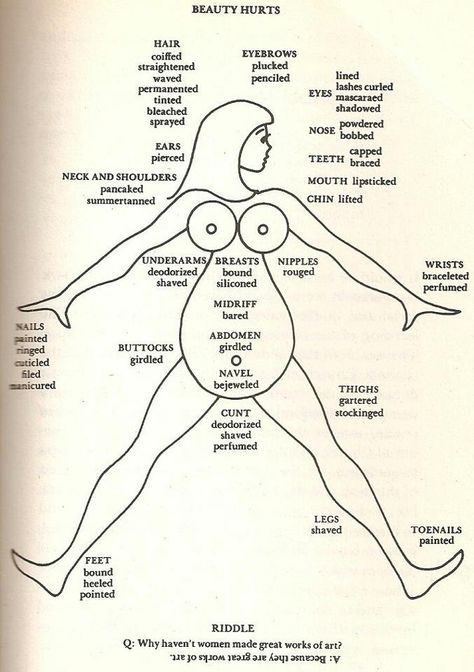

Now beauty practices have psychological effects on women too, she says, because the relationship between physical freedom and psychological development, intellectual possibility and creative potential, is an umbilical one. So she’s stressing again, what we’re able to think is going to be related to the way our body is tied down. Like other radical feminist critics of beauty she describes a broad range of practices that women must engage in to meet the dictates of beauty, and I’m just going to show you now the wonderful diagram from her book:

There we are, this is from the 1974 book Woman Hating, and you can see it says “Beauty Hurts” at the top, which is undoubtedly true. I think the little bit on the bottom says, “Why haven’t women made great works of art?” and the answer is “Because they are great works of art.” And this is the way that they are supposed to make themselves into works of art.

Now she says, the description she gives of what happens here, is that in our culture, and I think she’s writing about a culture here, not one part of a woman’s body is left untouched or unaltered, no feature or extremity is spared the art or pain of improvement: Hair is dyed, lacquered, straightened, permanented, eyebrows are plucked, pencilled, dyed, eyes are lined, mascara’d, shadowed, lashes are curled or false. From head to toe every feature of a woman’s face, every section of her body is subject to modification and alteration. And I remember when I first saw this diagram it had a considerable effect on me. Now I think, what are we missing? But at the time when I first saw it I thought that was very helpful, because it actually maps out what women take for granted, the extraordinary practices they perform on themselves every day, before they go out in the morning and so on. So many women take them for granted and it’s very important to actually have them mapped out here so we can see them.

Now today it would need to be supplemented with the more invasive and harmful practices that are becoming common in our times. So if we just look at what’s here then we can see what needs to go in. I thought it was quite interesting that she has actually got the navel bejewelled, I don’t know whether that means pierced, it probably does, but in 1974 not many women were piercing their navels. Now women are supposed to show their navels and have them pierced. So men are getting the sadomasochistic satisfaction of women’s pain and piercing just when they are walking round the street, sitting on the bus, and so on and so on, right. That’s very important.

Now here we have the cunt, that was the word we used at the time, I wasn’t tremendously keen on it then but there you go. The cunt, here, we have deodorised, shaved, and perfumed. Now we would have to say yes, completely shaved because women are doing Brazilian waxing to remove the hair entirely in Western cultures. I think they were probably just shaving bits around the edges in 1974, who knows. And labiaplasty, which is what’s going on now, which is that cosmetic surgeons take off women’s labia because women say they are unsightly or we get the explanation [from surgeons] that they get caught up inside during sexual intercourse and that’s uncomfortable. And I’m thinking, gosh, I used to be heterosexual, I can’t remember [anyone having] the problem! [laughter] Anyway, perhaps, apparently the labia hang out a little bit of the swimsuit. I’m thinking, why don’t we have swimsuits down here, I always wear, you know, summer wetsuits because I like to be covered up. You know you don’t have to have your labia hanging down the leg of your swimsuit [more laughter]. So obviously we would have to put labiaplasty in here.

Buttocks are girdled. I seem to remember my sisters and my mother had girdles, I didn’t actually wear a panty girdle as it was called in the 1960s. But now of course what women are supposed to do are extraordinary regimes of exercise to make sure they have a flat stomach, panty girdles are not really the way to go, but it’s all still going on. Breasts bound and siliconed, much more so, much more breast implants now than there ever was in 1974, nipples rouged and yes they probably have nipple rings in now because of that destruction of women’s bodies with piercing is absolutely de rigueur.

The face would be very different now because of course there’s lots of ordinary cosmetic surgery going on which is just like make-up now. Women are having botox in the face to paralyse their muscles, as an ordinary thing to do, every month you have it renewed and so on. So what I write about in my book is the way that the practices going on in 1974, and I did those practices too, what we have now is much more invasive, is now going in under the skin, drawing blood, and much more painful and brutal, than the practices that were happening at this time.

What Andrea also says about these practices is that “Beauty practices are vital to the economy.” Of course that’s true, there’s been hardly any work on how vital they are to the economy, and “They’re a major substance of male female role differentiation, the most immediate physical and psychological reality of being a woman.” In other words, they create sex difference. These practices–very harmful, painful, enormously expensive, time wasting and constricting to the body, and affecting what women can think–they create sexual difference. Otherwise how would we know who was on the top and who was on the bottom, and it’s crucial for male dominance that we know who’s on the top and who is on the bottom. Otherwise the system cannot work. So she explains that really well I think.

What I would like to do is criticise what’s going on in the culture now, and what I looked for, because I’m sad to say that this hasn’t changed, we haven’t suddenly got rid of sexual difference, women aren’t suddenly free to actually leave the house, both feet on the ground, hands in the pockets, not worrying about what they look like, bare faced, that’s not happened. That has not happened. It’s my wish for the future that it could happen, that women could have those human rights and freedoms that men have, just to be in the world, run down the street. It hasn’t happened.

So what I looked for, before coming away, I looked in the student union shop for magazines which showed pictures of men and women together, because what always astonishes me is when I see young people walking down the street and they’ve been on a night out or they’re going to a night out–the extraordinary sadomasochistic difference between them is really really clear between the women’s costumes and the men’s costumes. And it’s very very hard to find pictures of men and women together in women’s magazines, even celebrity magazines, because they’re all focused on the women. Right? I found a couple but forgive me if they’re not the clearest examples, it was what I could find at the time. And this is, I think it’s a Spice Girl:

Now, you will see the difference here, okay. The men are wearing loose suits, black shoes, and of course they have their mouths closed. Women’s mouths must be open so they can be penetrated at all times, and women’s bodies are open, right, so that’s really clear there. You have to go around going “Uh.” [laughter] I noticed this when I used to watch Dallas as a young girl, that the women have their mouths open, they say “Hello Deirdre, ah” and the men say, “Hello Deirdre, am.” [laughter] You will see here that the men are very very different from the woman. The woman in front, the Spice Girl, has got a lot of her body showing, she’s on incredibly high heeled shoes that would be immensely painful to her, and so on. So I think that even though she’s a celeb, its quite a good example I think, of what a lot of women would like to be, what they would like to look like and try to make themselves into when they go out. So what we have here is the sadomasochistic romance. I think this is extraordinary, and I think that a lot of people just accept it so much they probably wouldn’t even comment or think that was peculiar. I find it extraordinary, we’re in 2006, and this is what is going on. Women are in pain, totally disabled, showing their bodies, taking part in what I call the sexual corvee, which is, you know, how the peasants in medieval France, the serfs would have to do work on the landlords land for nothing in order to even cultivate their own land, this is what women have to do, it’s the sexual corvee, to create men’s sexual satisfaction on the streets and everywhere else they have to do this to their bodies, in order to have the right to, I think in terms of equal opportunities, these days, be in offices, have jobs, be out there in the world, this is the compensation, it’s the sexual corvee that they have to perform.

A couple more examples, this is apparently Madonna and her husband busy having a chat:

Perfectly ordinary picture, nothing peculiar, but I think it’s extraordinary. I think the shoes are extraordinary, the fact that she has to expose all her body and I assume she has shaved her legs in order to be able to do this, and so on and so on, and what she’s had to do with her hair, and her face, and the facial gestures are of course crucially important and we need to look at them as well. And she does have her mouth open; I don’t suppose they’d want to photograph her with her mouth closed. Mind you he’s got his mouth slightly open as well, it’s fair to say. Okay. [laughter] But I don’t think it’s because he wishes to be penetrated!

Here we’ve got a picture of a woman on her own:

I couldn’t find a man to go with her. She’s on her own but I’ve got her in because I thought it was kind of extraordinary. And I’d love to see a man in that costume! I think that would be great. Why don’t men go round in the evening in that costume? I mean, we’ve got equality, if that’s the situation, if we’re there now. Why aren’t men choosing, ’cause they tell us women choose these practices, choosing to do this? [laughter] Well they’re not, and I think it’s reasonable the men here could probably tell us why they’re not choosing to do this, yes, it’s degrading, it’s extremely painful, and it’s unpleasant. So that’s why they’re choosing not to do it. Okay.

I need to rush on. The cosmetic surgeons who do the cosmetic surgery also cut gender, inscribe gender, into the bodies of men who are trans-sexing, and trans-gendering. And the same surgeons take off the labia of women, and create the labia, supposedly of women, on men who are trans-gendering. And they’ve got websites where they offer all of this stuff. What they’re prepared to offer is getting more and more severe, I suspect at some time in the future they will be offering limb removal on demand, because this is the new thing, this is where we’re going. It’s called Body Identity Integrity Disorder, which is mostly men and I think many of them gay, who wish to have arms and legs removed, some of them wish to have all arms and legs removed, in order to become what’s called quads. Now if you look at the BIID website*, the surgeons and psychiatrists writing on that also do transsexual surgery, and they’re trying to get BIID into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual in the US, which would mean that they could legally take legs off, and in fact a surgeon in Scotland has taken healthy legs off two healthy men on demand. Okay? So eventually, there isn’t really a limit, I’m saying to you, to the extraordinary forms of aggressive surgery that are being carried out by cosmetic surgeons.

Now in response to the feminist rejection of beauty practices which Woman Hating encapsulates so well, I abandoned such practices for myself back in 1973. What caused me to do so was reading two books, Sexual Politics and The Female Eunuch, in 1970 to 71. Before that I had long, straight hair which hung over my face, like that. I didn’t want people to see my face, and it was dyed mid golden sable. I used all kinds of make-up, including many different colours around my eyes, false eyelashes, and so on. I depilated my underarms and legs, I wore high heels, I did all that stuff. I was heterosexual and I accepted that I must perform the sexual corvee.

Now, Andrea Dworkin of course abandoned beauty practices, and this is one of the most significant ways in which her detractors have always pilloried her. But her lifelong determination to reject what she called sex roles, and they’re now called gender, and femininity was an inspiration to other feminists always. Few American feminists in particular have rejected femininity entirely. Despite their important contributions in other ways, they have not rejected femininity as firmly and straightforwardly as Andrea did throughout her career.

So we live in a world in which social and political requirements are not just instilled into the minds of citizens through ideological control, but carved into their flesh. In particular the physical requirements that are seen to represent correct gender are carved onto women’s breasts, labia, lips, and onto the bodies of the men who decide they’re women. And the savagery of these practices is an indication that we’re living under a more exacting regime of gender. I will suggest to you that in many ways we are in a worse place, in relation to what’s called gender, than we were before. We are living under what I’d call a new regime of gender. The term gender wasn’t in common usage in the 1970s when Andrea was writing, and she uses the term sex roles. And I like the term sex roles because it makes it clear that the behaviours it describes are socially constructed. It’s a nice, straightforward term, it comes out of sociology. In the 1990s the term gender was adopted by many feminists to stand in for what had previously been called sex roles, i.e. the socially constructed behaviour which boys and girls are acculturated to adopt, in forms appropriate to their sex class categories. Some feminists went further and said the word “gender” was useful because it somehow contained within it the idea that men and women were involved in power relations in something called a “gender system,” or “gender relations.” I never quite understood that and I never liked the term “gender.”

What became clear very quickly was that the term gender experienced what’s called concept capture, in that it was appropriated by those with a very very different politics than feminism, and in fact in many cases anti-feminism. What happened in the nineties was that gender studies took over from women’s studies in universities; gender studies sections took over from women’s studies in bookshops. Meanwhile the term “gender” underwent this metamorphosis with concept capture and went back to the origins, the ways in which sexologists used it in the fifties, which was to describe gender in terms of cross genderism, the sexologists who dealt with transgenders in the fifties really used that term, and they gave it a biological basis, they said there was a biological substrate in the minds of men and women that meant that they could or couldn’t learn the correct gender behaviour. These days the way they explain transgenderism is to say that in the womb, the foetus–there’s no way to prove it so it has to be some kind of mystical thing you can’t prove–in the womb the foetus gets washed in a sudden burst of hormones one day, one morning maybe, and then from then on the person is going to feel they’ve got a different and wrong gender. All right? Can’t prove it, but that is seen as the biological basis of transgenderism today.

“Gender” became an alternative word for sex, so although sex was seen as biological by feminists and gender as socially constructed, eventually “gender” came to stand in for sex. You know that because at universities there are forms for instance that students have to fill in, and there are gender tick boxes, right: gender, tick the box, f or m. And of course, a lot of us would think, I can’t do that, I haven’t got a gender and I don’t want one. So you’re forced in to this, you know, when did you stop beating your wife situation, where you are not able to answer the question. Really, when offered gender, I mean my response would be No, Thank you, [laughter] but I’m not allowed to say on the form, No, thank you. It’s assumed now that gender is the same thing as sex, so gender has, you know, metamorphosed in the public mind.

Now another aspect of this concept capture is the development of a movement of transgender activists, originally called transsexuals. In the nineties this became transgenderism and became more general. Some queer and post-modern theorists would say that transgenderism includes various forms of transvestism, which is usually just the lead up to transgenderism, as well as actual transitioning and sex reassignment surgery. Now, transgenders are committed to traditional notions of gender for their excitement and apparently for their very identities, whereas feminists of the seventies and eighties considered that sex roles would have to be eliminated in the pursuit of women’s freedom. Transgenders seek to protect gender from criticism. They’re involved in what I call a “gender preservation movement,” and through changing legislation in Western countries they’re involved in a gender protection racket. All right? The best example of the gender protection racket is the 2004 legislation in the UK called the Gender Recognition Act, more about that in a moment.

Now gender has now been quarantined for use, not to do with women at all, in the context of transgenderism. There was a 2005 book, called Gender Politics by Surya Monro, published by Pluto Press, and it doesn’t deal with what Surya Monro says are called non-trans women. I think most of the women in this room are probably what are called non-trans women. Judith Butler now calls us bio-women. So as transgenderism actually creates a proper concept of real women, women who are not transgender now have to have a prefix in front of their name, they become non-trans or bio. Hello, Bio-Women! [laughter] In the book, it doesn’t cover women but it’s called Gender Politics, and she does cover sadomasochist and fetish citizenship, on the grounds of human rights. There needs to be human rights for sadomasochists and fetishists, but women are not in the book. Now this is all in a book called Gender Politics, so you can see how far we’ve come from gender being useful to women.

Now the “gender protection racket” has resulted in extraordinary legislation, as in the Gender Recognition Act. In this legislation the term gender is used as if it’s synonymous with sex. The Act enables men or women to come before a Gender Recognition Panel to get a certificate saying that they now have a different gender. The process doesn’t require surgery or hormone treatment, just documents from the medical profession, attesting to the fact that this person has done the real life test of wearing the clothes of the opposite sex. That’s all that’s necessary. One of the results of it is that female to male transsexuals, that is lesbians who have an interest in masculinity, can actually have babies after they’ve got a certificate saying they’re ‘Andrew’, right. So in the maternity ward we could have ‘Andrew’ over the door and Andrew will give birth to a baby. Transgender activists want Andrew then to be able to go down as the father of the child on the birth certificate. That’s not allowed in this legislation but that is what they would like. So that’s how far we’ve got. There are all sorts of other crazy elements of this legislation.

Now one of the things I find puzzling about it is that, when I look at the House of Lords debate on this legislation, those I agree with most are the radical right. Particularly the person I find that I agree with most, in here, and I’m not sure he will be pleased to find this, is Norman Tebbitt. Now, Norman Tebbitt is not having any of it, right, so in response to the Gender Recognition Act, he says, he gives a very good definition of gender as socially constructed and says, in your act you’ve got it confused, right, it should say sex and you’ve got gender. And Lord Filkin, for the government, who is putting this legislation through, says that sex and gender are the same thing and anyway, what does it matter? Right, isn’t that extraordinary? Tebbitt then accuses him of linguistic relativism. Which I love. [laughter] Couldn’t have put it better myself. Tebbitt also says that the savage mutilation of transgenderism, we would say if it was taking place in other cultures apart from the culture of Britain, was a harmful cultural practice, and how come we’re not recognising that in the British Isles. So he makes all of these arguments from the radical right, which is quite embarrassing to me, but I have to say, so called progressive and left people are not recognising the human rights violations of transgenderism or how crazy the legislation is. The legislation makes us engage in a folie à everybody, right? Everybody now has to go mad in order to understand or respond to this legislation.

Okay, what I am worried about is that in this new regime of gender, this very savage regime, we might all have to come before a gender recognition panel. The piece I am writing about this act at the moment is ‘They’ll know it if they see it, The Gender Recognition Act’. I mean if I come before the gender recognition panel, because the State is now regulating gender, it’s always regulated sex but now it’s got into gender, right. If I come before the panel what are they gonna say? I can’t say “no thanks” to them. So we’ve reached a rather dramatic stage where the State and legislation has got involved in regulating gender in incredibly traditional and very vicious, and I think, quite savage ways.

Right, I know I’m going to have to rush to the end. Why is all of that practice, the practice of transgenderism and that legislation acceptable? I think because there’s a very very deep-seated understanding within Western culture and perhaps all cultures, that something called gender does exist, must exist, cannot be got rid of, that there is some inevitable biological difference, doesn’t matter if it hops about and goes to the people you wouldn’t expect to have it, as long as it stays there. What cannot be imagined, is that gender could be got over, got through, and removed so that all women could have their feet on the ground. And that’s the crucial thing I think about Andrea Dworkin’s work and about Woman Hating, is she said, “We have to destroy culture as we know it.” Not accommodate gender with extraordinary legislation, terrible mutilating operations and hormones for the life of these unfortunate people who have been confused and destroyed by the gender system in which we presently live.

I’ll have to leave out everything else I was going to say and simply say at the end that reading Andrea Dworkin’s work makes me feel sane. It helps me to feel that it’s reasonable to work towards the elimination of gender, not tinkering, but actually working towards the elimination of gender. And it helps me in my conviction that feminism will come again. Looking back at 1974, the fact that we’re having this celebration, the fact that there are young women interested in the work of Andrea Dworkin, makes me feel more confident about the future. Thank you. [applause]

Please note: The photos were substituted as the photos shown by Sheila Jeffreys during the talk were not available.